The Geometry of AI Advertising: How Power Diagrams Could Replace Keyword Auctions

Written with Claude Opus 4.6 via Claude Code. I directed the research; Claude wrote proofs, ran experiments, built the prototype, and drafted prose. Idea to finished deliverables: one afternoon.

The most valuable advertising real estate in the world doesn’t have addresses.

When OpenAI launched ads in ChatGPT in January 2026, they opened a market of 800 million monthly active users and $20 billion in annualized revenue — all sitting in continuous embedding space with no keywords, no categories, and no existing auction machinery that fits. The industry is treating the ChatGPT ad auction as a product problem — which ad formats work, where to show ads, how to avoid annoying users. But underneath all of that sits an unsolved mechanism design problem: how do you run an auction when the thing being auctioned isn’t a keyword, but a region of continuous, high-dimensional space?

The answer comes from an unexpected place: computational geometry.

The formal version of this work is in the paper: Power Diagrams for Embedding-Based Ad Auctions (PDF). There’s also an interactive prototype where you can drag advertisers around and watch territories shift in real time.

Keywords Had Clean Markets

Google’s keyword auction is one of the most elegant market mechanisms ever deployed at scale. Here’s why it works so well:

“Mesothelioma lawyer” costs ~$200 per click. That price exists because the auction mechanics are clean. A keyword is a discrete, atomic biddable unit. You bid on it, or you don’t. There’s no ambiguity about what you’re buying.

Second-price auctions (and their Generalized Second Price variant) clear efficiently. The winner pays the second-highest bid plus a penny. This makes truthful bidding a dominant strategy — you should bid exactly what a click is worth to you. No game theory PhD required.

Budget forecasting is tractable: count the number of times your keyword gets searched, multiply by your expected win rate, multiply by your bid. You can predict next month’s spend within 10-15%.

This clean machinery generated $238 billion in Google search ad revenue in 2025 (Alphabet Q4 2025 earnings). It works because keywords are discrete, countable, and unambiguous.

Embeddings Break Everything

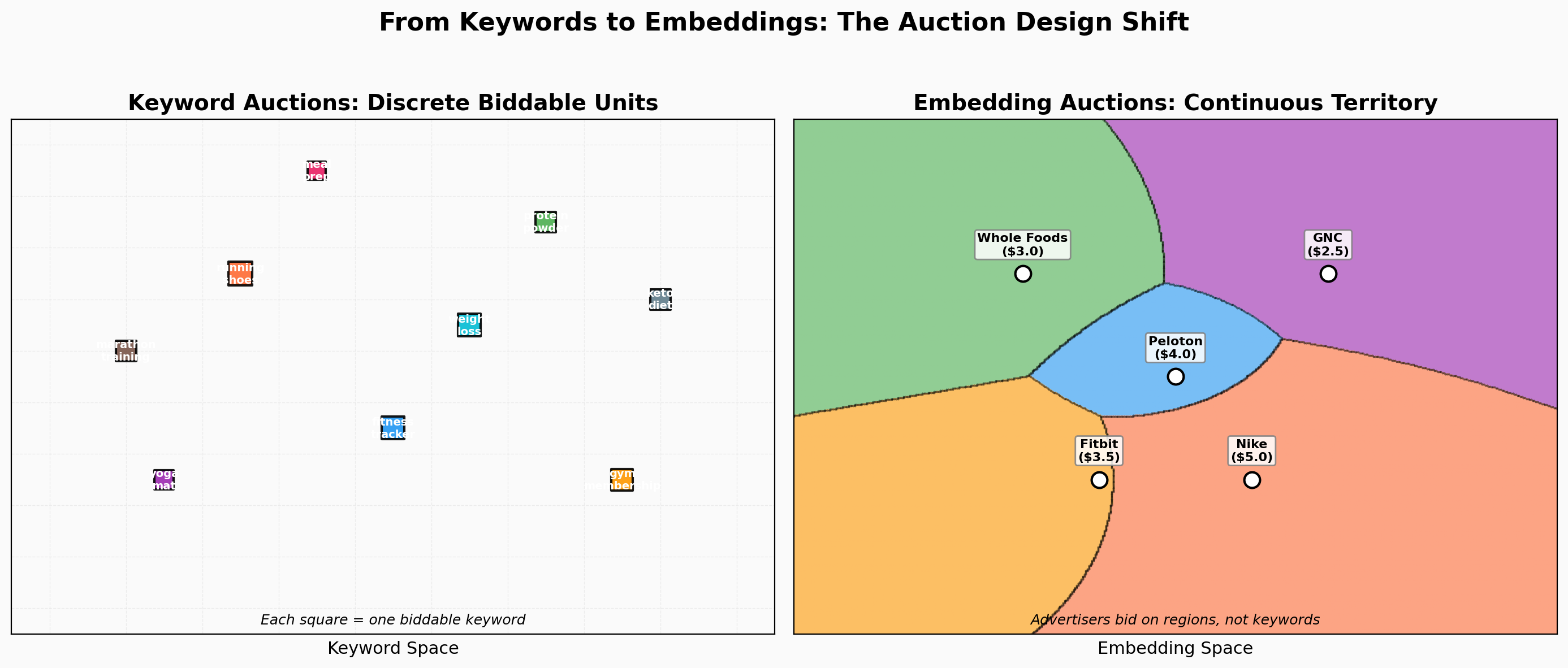

A ChatGPT conversation isn’t a keyword — it’s a trajectory through continuous space.

When a user asks “What’s a good running shoe for someone training for their first marathon who has flat feet and a budget under $150?”, that query doesn’t map to a single keyword. It maps to a point in high-dimensional embedding space — a point that encodes topic (running, footwear), intent (purchase-ready), specificity (first marathon, flat feet), and price sensitivity (budget constraint) simultaneously.

An “impression” in this world is a point in continuous space. And advertisers don’t want a keyword — they want a region.

Nike wants every conversation about running shoes. But they also want conversations about marathon training, fitness gear comparisons, and athletic lifestyle content. Their interest isn’t a list of keywords — it’s a fuzzy, continuous region of embedding space that bleeds into adjacent topics.

Two advertisers compete fiercely for “running shoes” conversations but not at all for “trail running philosophy” conversations. Their regions of interest overlap in complex ways. And the dimensionality isn’t just semantic: time of day, user demographics, intent signals, device context, and conversation history all matter. Advertisers are bidding on high-dimensional manifolds, not keywords.

Three things that worked cleanly with keywords now break:

- What do you bid on? There’s no discrete unit. You can’t enumerate “all possible conversation embeddings.”

- How do you clear the market? Overlapping fuzzy regions don’t have clean winner determination.

- How do you predict spend? Your win rate depends on the complex geometry of every competitor’s value function.

The Geometric Solution: Power Diagrams

Here’s the end-to-end picture. An advertiser says: “I want budget-conscious marathon beginners.” The platform embeds that description into the same continuous space as user conversations — it becomes a point (center) with a radius (reach). A bid determines how much territory that point commands. The power diagram partitions the entire embedding space into advertiser territories, and VCG payments tell each advertiser what their territory costs. Natural language in, price out, geometry in the middle. No keywords. No categories.

The math that makes this work: if you model each advertiser’s value for an impression as a function of distance in embedding space, the optimal allocation has a known geometric structure called a power diagram.

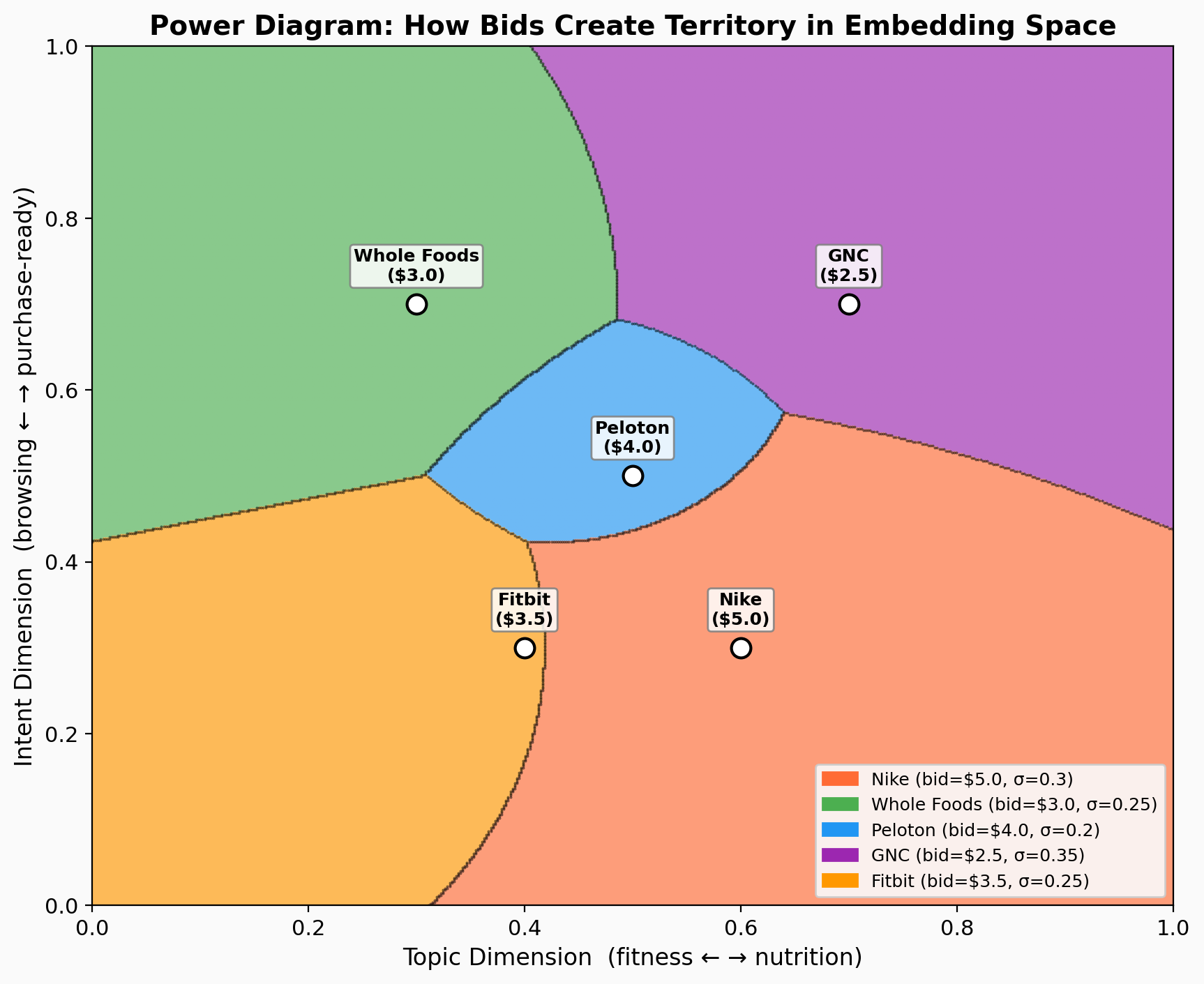

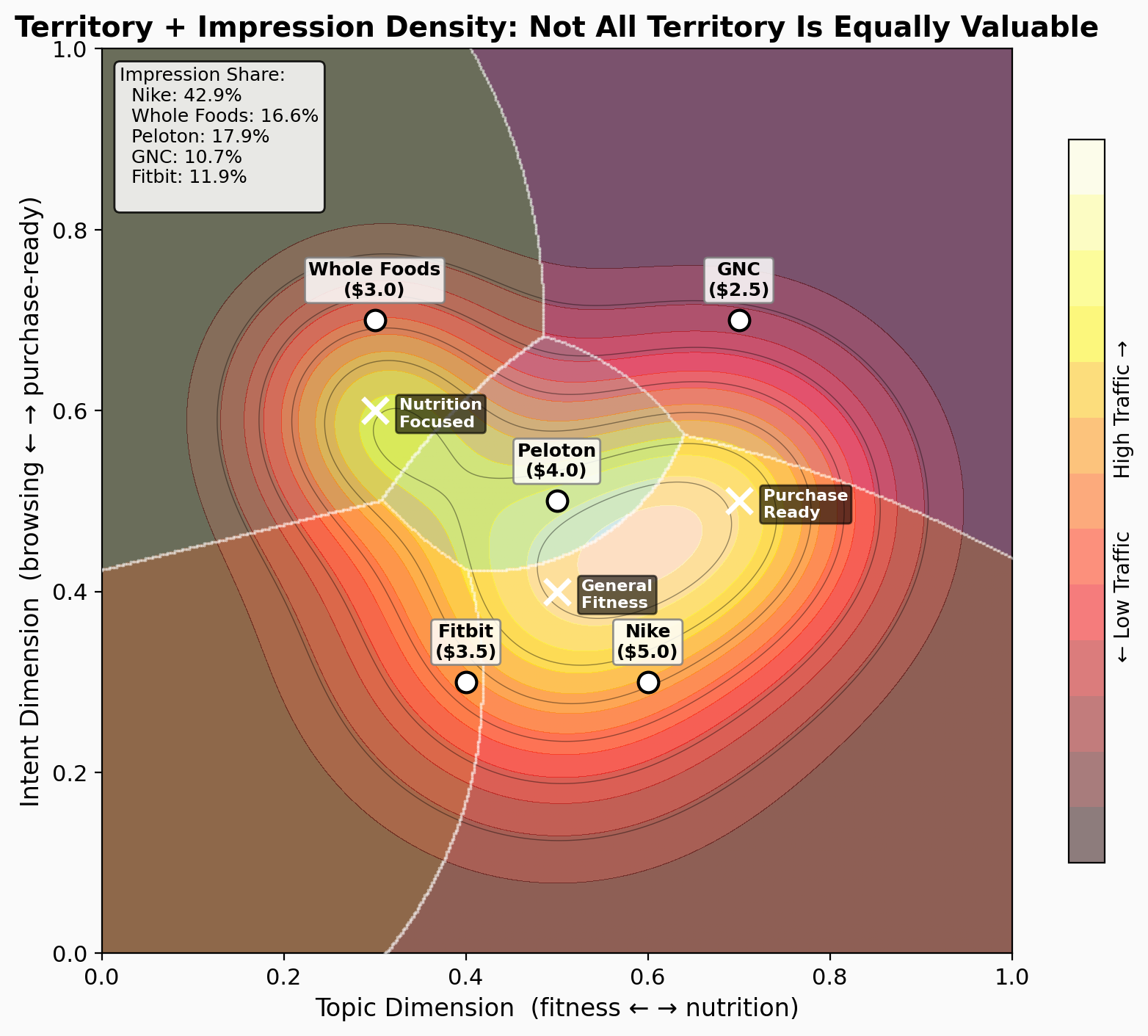

Imagine a 2D map representing a slice of embedding space — say, “topic” on one axis and “intent” on the other. Each advertiser sits at a point on this map (their ideal customer) with a bid that determines how far their influence extends.

The partition of space into advertiser territories follows a simple rule: at any point, the winner is the advertiser with the highest bid-adjusted proximity. Formally, for each advertiser i with center c_i, bid b_i, and reach parameter σ_i, the score at point x is:

score_i(x) = log(b_i) - ||x - c_i||² / σ_i²

The advertiser with the highest score wins the impression. This creates a power diagram — a generalization of Voronoi diagrams where weights (bids) shift the boundaries.

A concrete example. Suppose Nike sits at center (0.6, 0.3) with bid $5.00 and reach σ=0.3, and Peloton sits at (0.5, 0.5) with bid $4.00 and σ=0.2. At point x=(0.45, 0.35):

Nike’s score: log(5.0) − (0.45, 0.35) − (0.6, 0.3) ² / 0.09 = 1.61 − 0.28 = 1.33 Peloton’s score: log(4.0) − (0.45, 0.35) − (0.5, 0.5) ² / 0.04 = 1.39 − 0.63 = 0.76

Nike wins this impression. Its higher bid and closer proximity both contribute. Move the point toward (0.5, 0.5) and Peloton’s proximity advantage eventually overcomes Nike’s bid advantage — that crossover is the power diagram boundary.

The key properties:

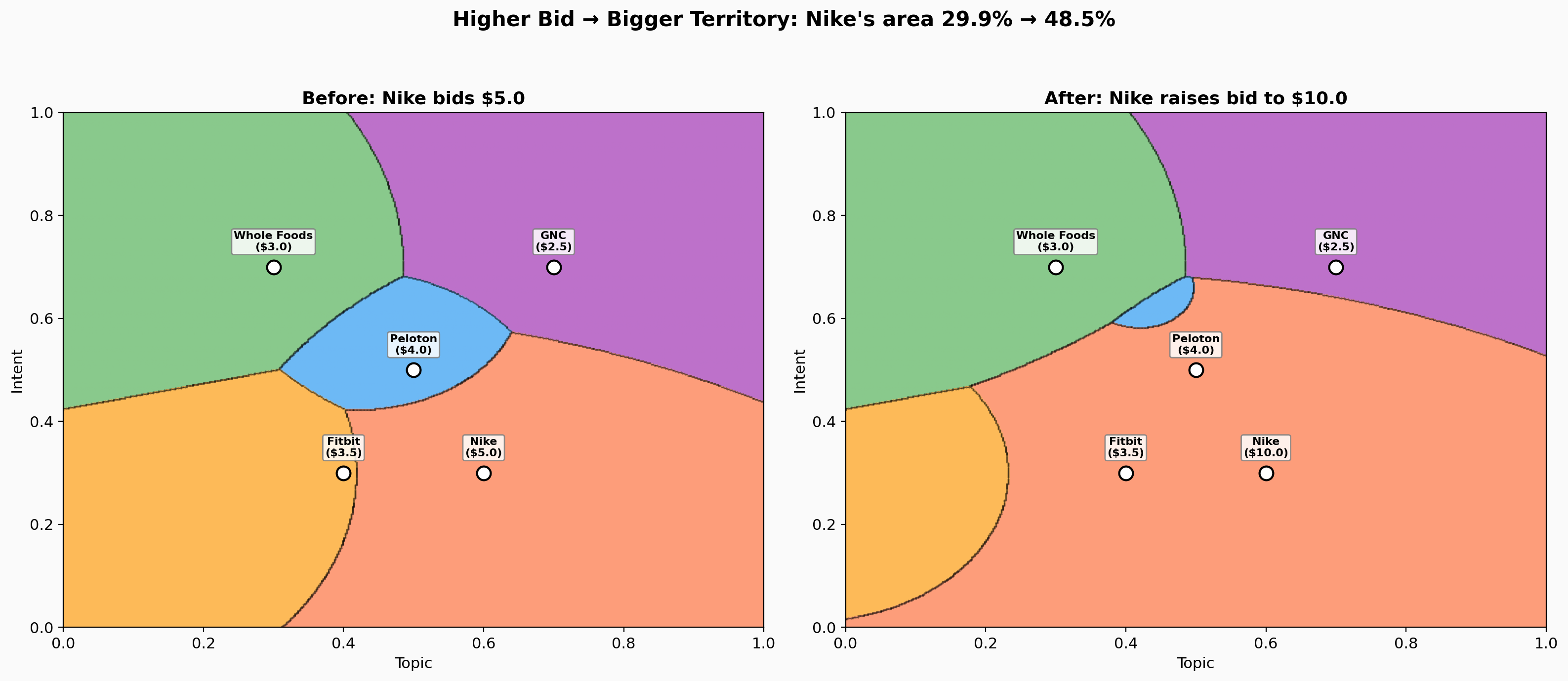

- Higher bids = bigger territory. Doubling your bid pushes your boundaries outward, capturing more of the embedding space.

- Boundaries are where bid-adjusted distances equal. The border between Nike and Peloton sits exactly where Nike’s bid advantage equals Peloton’s proximity advantage. These boundaries are hyperplanes (straight lines in 2D).

- The math is well-studied. Power diagrams have been used in computational geometry since the 1980s. Algorithms for constructing them, querying them, and computing integrals over their cells are known and efficient.

When Nike doubles its bid from $5 to $10, its territory expands from 30% to nearly 50% of the space — eating into every competitor’s region. This is the continuous analog of outbidding someone on a keyword, except the “outbidding” happens along a frontier, not at a single point.

Why It Gets Hard

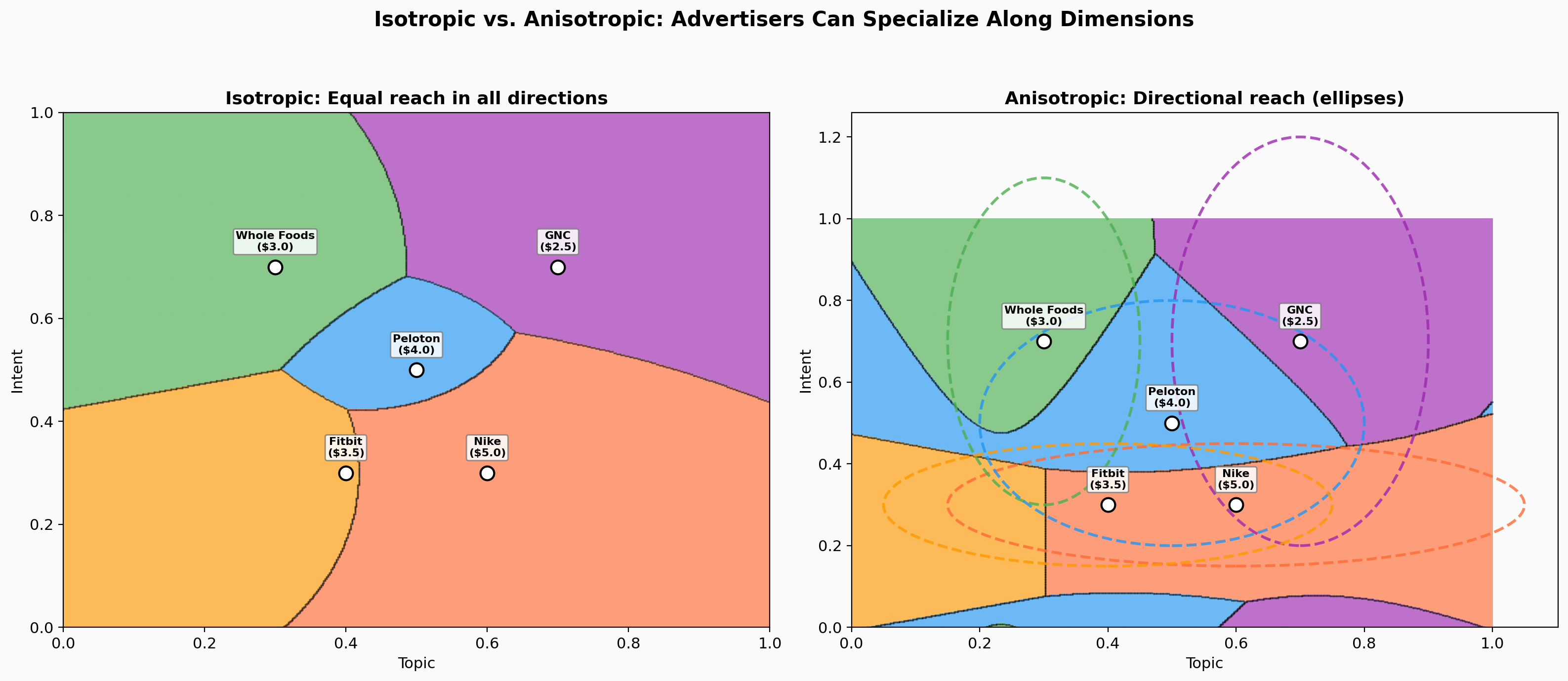

The clean power diagram story holds when advertisers have isotropic preferences — they care equally about all dimensions, their value function is a symmetric bell curve around their ideal point. Real advertiser preferences are messier.

Anisotropic preferences. Nike cares far more about purchase intent than about the specific sport. Their value function is stretched along the intent axis — an ellipse, not a circle. When advertisers have directional preferences, boundaries become quadric surfaces (curved lines in 2D). Still computable, but the clean hyperplane structure is gone.

Multimodal preferences. A bank wants “mortgage calculators” conversations AND “retirement planning” conversations — two separate clusters in embedding space. Their value function is a mixture of Gaussians. Now boundaries are level sets of Gaussian mixture sums — they can be arbitrarily complex. The clean geometric structure breaks down entirely.

Real-time constraints. An ad auction has to determine a winner in under 10ms (GumGum’s production target for contextual ad serving). For the isotropic case, you can precompute a spatial index and find the winner in O(log N) time. For the anisotropic or mixture case, you’re back to evaluating every advertiser — O(N) per impression. At scale with thousands of advertisers, this blows the latency budget.

The progression from isotropic to anisotropic to mixture preferences is a progression from tractable to hard:

| Preference Type | Boundary Shape | Winner Determination | Incentive Compatible? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isotropic Gaussian | Hyperplanes | O(log N) | Yes (VCG) |

| Anisotropic Gaussian | Quadric surfaces | O(N) | Approximately |

| Mixture of Gaussians | Arbitrary level sets | O(NK) | Open question |

The Real Estate Analogy

The embedding space of a major LLM platform is best understood as real estate.

Different regions have wildly different property values based on user traffic density. The “general fitness” neighborhood gets heavy foot traffic; the “niche hobby” neighborhood is quieter but the visitors who come are deeply engaged.

Not all territory is equally valuable. In the power diagram above, notice that Peloton (blue) controls the smallest area but sits in the densest traffic region — its 5.3% territory captures 17.9% of impressions. Nike controls the largest area, but what matters is the impression-weighted territory — how much user traffic flows through your region. An advertiser with a small territory in a high-traffic area captures more impressions than one with a vast territory in a quiet corner.

The analogy extends further:

- Zoning: OpenAI excludes politics, health, and mental health from ads — these are exclusion zones, regions of embedding space where no advertiser can operate.

- Leasing, not buying: Your territory shifts as competitors adjust their bids. Raise your bid and your boundaries push outward. A new competitor enters and everyone’s territory shrinks.

- Property value shifts: Cultural trends, seasonal events, and breaking news change the traffic patterns through embedding space. “Running shoes” gets more traffic in January (New Year’s resolutions) than in November.

- Generative ads: In the LLM context, the same product can get different pitches depending on the “neighborhood.” A running shoe ad near a “beginner marathon training” conversation sounds different than one near a “competitive ultrarunning” conversation. The ad creative itself is a function of position in embedding space.

What Industry Does Today (And Why It’s Suboptimal)

The current industry approach to contextual ad targeting in continuous space is simple: discretize it.

The IAB (Interactive Advertising Bureau) maintains a content taxonomy of 698 categories (IAB Tech Lab Content Taxonomy v3.0). Every page, video, or conversation gets classified into one or more of these buckets. Advertisers bid on buckets. Standard RTB (real-time bidding) auctions run on each bucket.

This works. It’s fast, compatible with existing ad infrastructure, and advertisers understand categories. Companies like Seedtag and GumGum use embeddings internally for classification — GumGum targets <10ms end-to-end latency — but still output IAB categories for the auction layer.

But the value proposition of embedding-based ad targeting is precisely the nuance that discretization throws away. Consider two conversations:

- “What protein powder tastes good in smoothies?” → IAB: Health & Fitness / Nutrition

- “I need a high-protein meal plan for marathon training on a budget” → IAB: Health & Fitness / Nutrition

Same category. But the second user is further along the purchase funnel, has a sports context, and is price-sensitive. An advertiser selling premium protein powder should bid much more on the first; a budget sports nutrition brand should bid more on the second. With category-level targeting, both get the same treatment.

The discretization problem also creates boundary artifacts. A conversation that sits right on the edge between “Sports” and “Nutrition” gets arbitrarily assigned to one, losing the information that it’s relevant to advertisers in both.

Running a continuous ad auction natively in embedding space — power diagrams instead of category buckets — preserves this information. The boundary between two advertisers isn’t a hard category line but a continuous frontier shaped by their bids and preferences.

The Open Research Agenda

What I’ve described is a framework, not a solution. Turning power diagrams into a deployed ad auction system requires solving several hard problems that sit at the intersection of computational geometry, mechanism design, and machine learning:

Representation. How do advertisers express preferences over continuous high-dimensional space? The isotropic Gaussian model is tractable but limited. Mixtures of Gaussians are expressive but intractable. Is there a sweet spot — a parameterization that’s expressive enough for real advertisers, structured enough for efficient market clearing, and transparent enough for budget management?

Incentive compatibility. In keyword auctions, VCG (Vickrey-Clarke-Groves) payments make truthful bidding optimal. In the isotropic power diagram case, a VCG analog exists. But for anisotropic and mixture preferences, the incentive properties are unclear. Can you design payments that approximately preserve truthfulness when value functions are complex?

Budget pacing. In keyword auctions, budget management is straightforward: you know your win rate per keyword, you can predict spend. In power diagram auctions, your spend depends on the geometry of all your competitors’ value functions. If Nike raises their bid, Peloton’s territory shrinks, Peloton’s budget drains slower, Peloton can eventually sustain higher bids, and Nike’s territory shrinks back. How do you give advertisers reliable budget forecasting in this setting?

Computational tractability. Real-time auctions need winner determination in under 10ms across thousands of advertisers. The isotropic case admits fast spatial indexing (kd-trees, ball trees). The general case requires approximation schemes — quantizing the anisotropic case into multiple isotropic virtual advertisers, trading fidelity for speed.

Dynamic equilibrium. Keyword auctions reach approximate equilibrium quickly because the strategy space is simple. In continuous space, the strategy space is infinite-dimensional. Do power diagram auctions converge to equilibrium? How fast? What does the equilibrium look like?

These aren’t theoretical curiosities. They’re engineering constraints that determine whether embedding-native ad auctions deploy at scale. The academic literature has pieces of the puzzle — optimal transport theory, computational geometry, neural mechanism design — but nobody has assembled them for this application.

The Game Theory: Who’s Playing, and What’s Stable?

Mechanism design gives us the auction rules. But rules don’t exist in a vacuum — they create a multi-player game between advertisers, the platform, and users. Whether the whole system reaches a stable equilibrium is a harder question, and the real estate analogy helps think through it.

Advertiser vs. Advertiser: Territorial Disputes

In our power diagram model with VCG-like payments, truthful bidding is a dominant strategy — you can’t gain by lying about how much an impression is worth to you. So far so good.

But advertisers don’t just choose a bid. They choose where to plant their flag and how wide to cast their net. An advertiser can profitably misreport their center. Concretely: if impression density peaks at (0.5, 0.4) and Nike’s true center is (0.6, 0.3), Nike gains by declaring (0.55, 0.35) — shifting toward the traffic peak. Under VCG, this costs them on impressions near their old boundary (where their true value was marginal anyway) but gains them high-density impressions in the shifted region. The net effect depends on the density gradient — steep gradients make misreporting more profitable.

VCG payments self-penalize this somewhat: you win impressions you don’t actually value, and you pay for the disruption you cause to neighbors. But the penalty is imperfect. The full strategic game — over position, reach, and bid simultaneously — lives in an infinite-dimensional strategy space. Whether it converges to equilibrium at all is an open question.

The Hotelling model from spatial economics predicts what the landscape looks like if it does converge: advertisers spread out along the most valuable dimension (probably purchase intent) and cluster on secondary dimensions. Picture a commercial strip where every store is on the same street but at different addresses — fierce competition for foot traffic along the main road, tacit coexistence on the side streets.

Platform vs. Advertisers: The Information Landlord

The platform is the landlord who sets the rules and controls what tenants can see. This is where the power asymmetry matters most.

The platform observes all N bid vectors simultaneously — every advertiser’s center, reach, and bid, plus the full traffic density map. Each advertiser sees only their own win rate, spend, and a black-box “estimated reach.” This is N² information vs. N information — a fundamental asymmetry that grows quadratically with the number of competitors. The platform can set opaque reserve prices (minimum bids below which territory goes unallocated — artificial scarcity), offer “bid suggestions” that happen to maximize platform revenue, and reveal just enough information to keep advertisers bidding without letting them fully optimize.

This is Google Ads today, but harder for advertisers to reason about. With keywords, an advertiser can at least see what they’re bidding on. In continuous embedding space, the thing you’re bidding on is abstract and high-dimensional. The platform effectively controls the map, and the tenants can only see their own lease terms.

The revenue-maximizing play (Myerson’s optimal auction) would involve the platform strategically leaving some territory unallocated — the equivalent of a landlord keeping units empty to drive up rents in the rest of the building. Whether platforms actually do this depends on competitive pressure.

Platform vs. Users: The Zoning Board Problem

OpenAI’s tiered pricing (free with ads, Plus/Pro without) is a self-selection mechanism. Users who value their attention most reveal this by paying for premium. Users remaining on the free tier have revealed they’ll tolerate ads for free access.

This is an elegant sorting equilibrium — and it makes the ad business more viable than it otherwise would be. The users who’d be most annoyed by ads have already left the ad-supported tier. The platform can push ad load higher for the remaining users because the most ad-sensitive people have self-selected out.

But the real estate analogy reveals a darker dynamic. The platform is simultaneously the landlord (selling territory to advertisers), the city planner (designing the space users navigate), and the tour guide (generating the conversational content). These roles conflict.

If generative ads mean the platform creates ad copy tailored to the user’s position in embedding space, then the platform has a subtle incentive to steer conversations toward high-value advertising neighborhoods. “Tell me about running shoes” is worth more to the platform than “tell me about Stoic philosophy.” OpenAI explicitly claims “answer independence” — that ads won’t influence responses. But the incentive is structural and ongoing. It’s the equivalent of a city planner who also happens to own commercial real estate: the zoning decisions will always be suspect.

Does the Whole System Reach Equilibrium?

In the short run, probably yes. VCG-like payments keep advertiser bidding roughly honest, tiered pricing sorts users into appropriate tiers, and the platform extracts rent via information asymmetry and reserve prices. The power diagram stabilizes into a reasonable partition.

In the long run, three forces make the equilibrium fragile:

Budget depletion cascades. Territory shifts are continuous functions of bids — power diagram boundaries move smoothly with weights. But budget depletion is discontinuous: an advertiser either has budget remaining or doesn’t. When Nike raises its bid, Peloton’s territory shrinks, Peloton’s budget drains slower, Peloton can eventually sustain higher bids, and Nike’s territory shrinks back. This mismatch between continuous territory dynamics and discontinuous budget constraints is what creates oscillation. The “equilibrium” is likely a limit cycle, not a fixed point — the continuous-space analog of the boom-bust cycles observed in real estate markets.

Platform competition. Unlike social media, LLM platforms have weak network effects. If Perplexity offers “fewer ads, same quality,” users can switch easily. This keeps ad load in check but means the equilibrium is sensitive to competitive entry. No one platform has the lock-in that Google has with search.

The content steering problem. If users ever notice that free-tier answers are subtly biased toward advertisable topics, trust collapses overnight. This isn’t a game-theoretic equilibrium problem — it’s a commitment problem. The platform has to credibly tie its own hands, and it’s not clear what enforcement mechanism exists beyond reputation.

Honestly? Nobody knows if a stable three-player equilibrium exists in this setting. The pieces that are well-understood — VCG for truthful bidding, Myerson for revenue optimization, Hotelling for spatial competition — don’t compose cleanly when you combine continuous space, generative content, and multi-sided platform dynamics. The real estate analogy is useful precisely because real estate markets also don’t have clean equilibria — they have cycles, bubbles, regulation, and path dependence.

This is the most important open question in the space: not “how do you compute the power diagram?” but “does the game it creates actually converge to something stable, or is embedding-space advertising inherently turbulent?”

This Is a New Field

The shift from keyword to embedding-based advertising — exemplified by the ChatGPT ad auction challenge — isn’t incremental. It’s a change in the mathematical foundations of how ad markets work. Keywords gave us discrete combinatorial auctions. Embeddings give us continuous geometric allocation problems. And the game theory of continuous territorial competition is far less understood than its discrete counterpart.

Power diagrams are the natural starting point for embedding-based ad targeting — they’re the continuous analog of keyword auctions, with clean properties in the isotropic case and a clear path toward more expressive preference models. But the full problem of a continuous ad auction — expressive preferences, incentive compatibility, budget management, real-time computation, and multi-player equilibrium — is wide open.

The ChatGPT ad auction alone could be a $10B+ annual market within five years, based on 800M users and Google’s ~$0.30 average revenue per search user per month. The company that solves the geometry owns the auction infrastructure. The company that solves the game theory owns the market. These might not be the same company.

The accompanying paper, Power Diagrams for Embedding-Based Ad Auctions: Mechanism Design in Continuous Intent Space (PDF), provides formal proofs and experimental results. The game-theoretic analysis in this post is speculative and intended to map the problem space, not to claim settled conclusions.