What a Startup is not

When a startup makes the news, the headlines point to metrics like funding, user count, or revenue. It’s easy to think that those are goals to aspire to, but those metrics tell a growth story after having found their Product-Market-Fit (PMF). It doesn’t tell the story of how they found it. It’s a rear-view-mirror view of their growth. But if not growth, what is a startup, pre-PMF?

|

|---|

| How it feels to read startup news sometimes |

The purpose of a startup is to prove that a profitable business can exist. It’s not to make lots of money, or to get famous, or to get funding to elevate your status. What’s the difference? Here’s a fable:

Imagine that you are a farmer before the industrial revolution, hoping to get rich with a new variety of apples. Your neighbor found a variety of grapes that he sells to wineries, so you’d think you can do the same for cider. When you look over to your neighbor, you observe that he has a large harvest operation with lots of workers, making deals over fancy wine, exercising top-down control over the operations. It’s dirt, rain, and sunshine printing money.

|

|---|

| Your neighbor making bank with his new grapes |

If he can do it, why can’t you? So you go out to build the same thing he’s got, but with apples instead. You dedicate months and years of your life, making a new apple variety, setting up apple trees, hiring workers to harvest them, trying to make deals with cideries.

|

|---|

| Where’s the money? |

But it turns out that the apple variety you developed are too sour for cider, turn mushy quickly, and not so sweet. But instead of thinking that you should start over with a different variety, you suffer from sunk cost fallacy and double-down on the original variety and try to sell it for making vinegar, or animal feed. Eventually, you run out of money and patience and go back to growing wheat and corn instead.

It’s much more common for startups to fail pre-validation than for them to achieve success and scale. Yet, we look to those on the podium, unaware of survivorship bias. Successful businesses are successful because they got lucky. But if you look at the people that started those businesses, you will find that most of them had a string of failures leading up to their success. The failures do not guarantee future success, but it certainly seems to help build the knowledge and experience. They learn effectively from their failures.

This is a total re-frame from a layman’s view of what makes a startup effective. Instead of using metrics that indicate an already-successful business, a startup should seek to improve odds of success in a series of trials instead. The best way to improve those odds is to fail as efficiently as possible, and to not stop. To fail efficiently means to conduct experiments that produce maximal surprise in a short time. For an apple strain developer, that means making lots of variations and pruning the bad ones, and generating more varieties from the lessons learned.

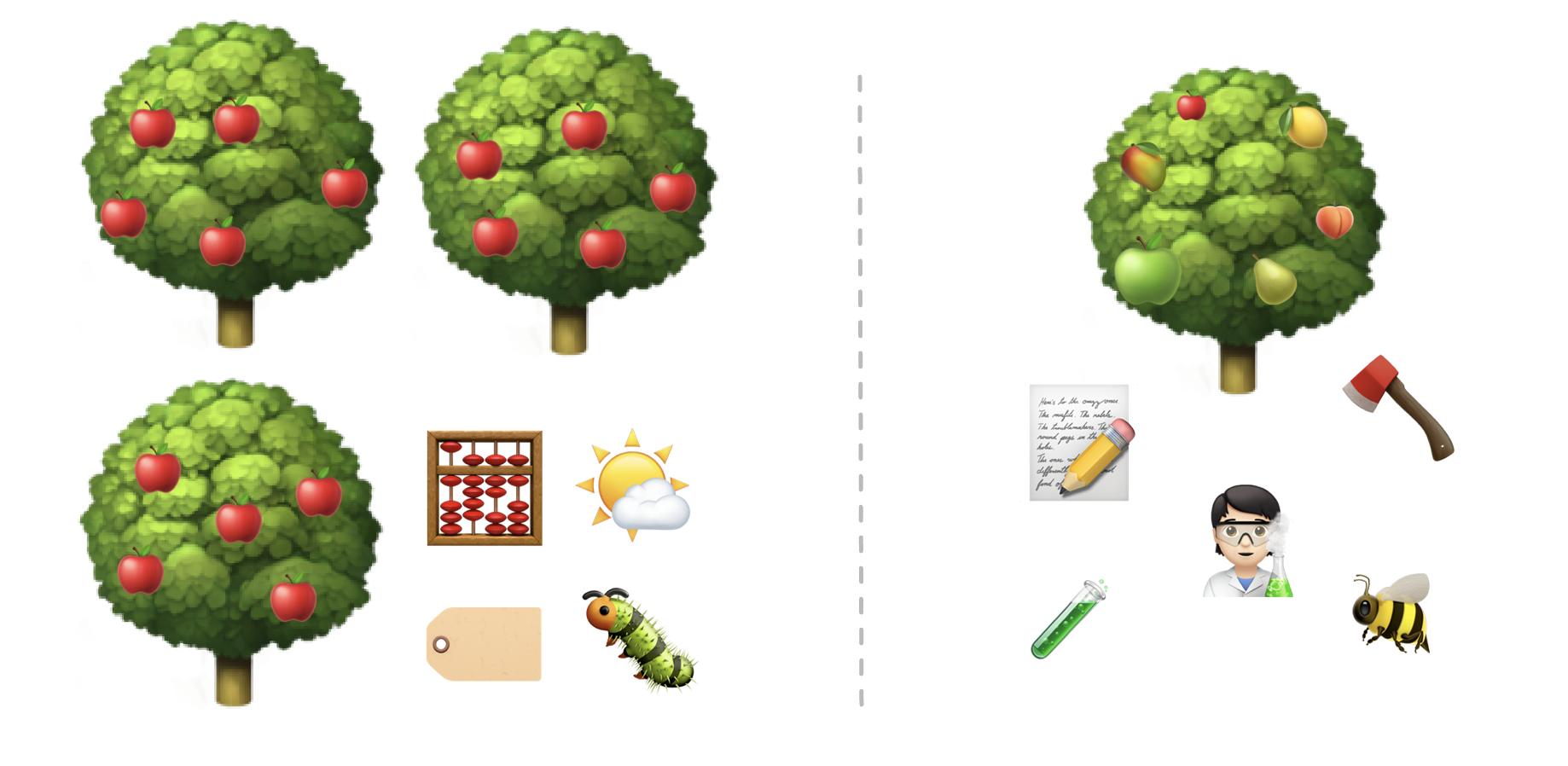

|

|---|

| Tools in production vs. tools in a startup |

Notice that the shift in goals completely flips the nature of work. Worrying about yields, costs, and size of the operation will direct efforts towards incremental improvements in measurable ways. But in a startup, bugs and unit costs are noise, not problems. Nobody cares about bugs in bland apples. And it doesn’t matter how many total apples were sold; it matters a lot more how likely a cidery is willing to buy your apples.

So if your pre-PMF startup is emulating the success of established companies by using the same tools, processes, and metrics, it’s counterproductive to proving a business. It’s actively resisting failures, by diluting and delaying the signal needed to move on to the next experiment. Expect failures, embrace lessons, and prepare to pivot.