Reflecting on Little Bird

The company is still in stealth, so I redacted the name

Little Bird (LB) is a startup and a chat client product aimed at professionals. By listening in on your desktop and browser activity, it retains memory of your activities throughout the day and acts as a second brain — an executive assistant backed by the near-limitless intelligent capabilities of frontier LLM models.

I joined LB just a few short months ago in late 2024 as a software generalist who happens to love using Swift. A contract-to-hire, I delivered on the requests from leadership on what I believed to be a clear path to product market fit (PMF). I’m now laid off, as with most other members I met at the time I joined.

Timing Growth

As any successful startup would aspire, growth happened. I wish we got the kind of growth that indicated a tighter product market fit, but we grew in other ways; we grew in employee count. I witnessed this happen at Fast one-click pay (Blog post).

At the time of my leave, LB had two designers, three PhD scientists working the AI side, ~20 engineers, one marketing, one growth, all before we had revenue. From what little I know of startups, sales revenue is the ultimate validation.

If capital efficiency was the only concern, then it would have been the founders’ and finance’s problem, but engineering doesn’t grow linearly with more people. From my experience, having more people actually slowed us down. In anticipating merge conflicts and heated discussions about code architecture, I often yielded my opinions to those who were willing to put in more work. Because we worked remote async, the window of time to hash out our disagreements were limited to only half the work day.

In another instance, I was having disagreements about prioritizing readability vs. testing. I advocated for tests over readability because tests enable refactoring and mitigate regressions. Another engineer disagreed with me, but I wasn’t going to spend half an hour agreeing to disagree. The migration ended up skipping on tests as a result.

Investing into employees and their salaries at a startup is like buying call options on the company. Employee yields are invisible to the investor until it hits the market and starts making money. Is pre-PMF the right time to ramp up investment?

Clarity of purpose

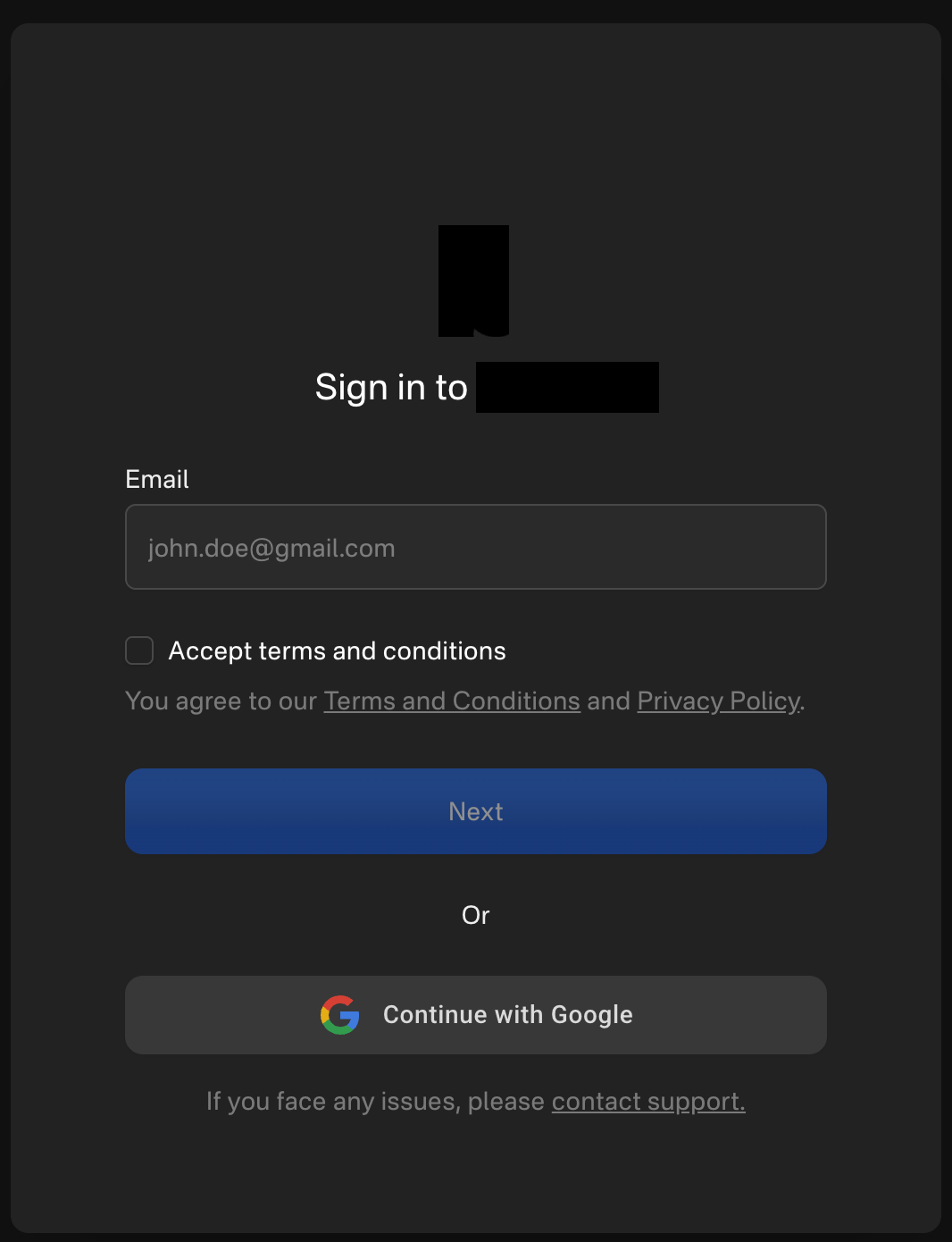

As an engineer, I didn’t get front-row seats to user conversations but I did see the notes. People were seeing value and intrigue from an LLM that can reacll memories and synthesize todos. It was obvious that we had something magical on our hands. Naturally, we kept pushing for a better product, hoping that we’ll get more users. Some infra/backend engineers moved us to containerization. Anticipating scalability, other engineers migrated from async Python to Temporal Workflows. We re-implemented authentication with Auth0. Designers translated the founders’ vision of the perfect chat client into Figma designs, three times over.

On its face, these were all startup product activities. But it was missing a direct connection to the purpose of a pre-PMF startup: to prove a business model. Instead of aggressively proving that the user needs are valid, and that building the glove-fit perfect for that need, we were guided by leadership vision and fixing broken features.

Had we focused on validating the users’ needs for an LLM with long-term memory that’s also an executive assistant, we would have put up a pay wall, and user interview summaries would be the topic at planning. PMF is invisible, but the app and the code artifacts are easy to point to. It’s an easy mistake that (nearly) every founder experiences.

Quality standards

In my first month, I worked on parsing dates from messaging apps. I wrote unit tests for them, and on the firt day of January, the tests that were passing the day before started failing. Had I not written tests, those would have kept failing. Tests caught those regressions, and user impact went unnoticed. In my second month, I wrote tests for the backend because there were none. I was quite pleased with myself, thinking that I set a standard for testing in the engineering team.

But as more people joined, what little quality culture we had eroded, and no new tests were written. In fact, when we migrated to Temporal Workflows, the old tests got deleted and were never rewritten. And when frontend went through a redesign, the checklists (manual test) went forgotten.

Do tests prevent regressions? That depends on what it covers and if it’s maintained. When a test fails, the engineer asks himself: To fix or to delete, that is the question. A the coverage dwindles, regressions are inevitable. Weeks can pass without anyone noticing that the feature that they worked so hard on was broken.

Quality is a culture upheld by standards mutually agreed to be sacred. When there is no fear of regressions, without remediation to fix the systemic issue, the leaky bucket will reach a product equilibrium where more engineering effort is allocated to its stability than its growth.

My responsibility

It’s easier to paint myself as a fallen hero, but I certainly wasn’t a perfect employee. I should have pushed back harder on tests, and not approve untested pull requests so carelessly. I could have aligned my team on purpose, and have more frequent discussions on purpose with leadership. I would have asked to be part of hiring strategy, but I was too timid to ask.

But on the other hand, I’m not the founder, or an investor. I didn’t even cliff a full year of equity vesting. The best I can do is reflect, learn, and to warn others of the same. Thanks for reading.