Buying Space, Not Keywords: A UX for Advertising in Embedding Space

Written with Claude Opus 4.6 via Claude Code. I directed the design; Claude built the prototype, generated diagrams, and drafted prose.

In keyword advertising, you buy words. You pick “running shoes” from a list, set a bid, and wait for someone to type those exact words. The system is discrete: each keyword is an independent auction, and your targeting decisions are a series of checkbox selections from a finite menu.

Embedding-based systems don’t work this way. Modern language models map every piece of text — every query, every conversation, every page — into a continuous vector space with hundreds or thousands of dimensions. OpenAI’s text-embedding-3-large uses 3,072 dimensions. Cohere’s embed-v4 uses 1,536. Google’s gemini-embedding-001 uses 768. In this space, “best running shoes for flat feet” and “marathon training plan” aren’t separate items in a catalog — they’re nearby points in a continuous manifold, separated by a measurable distance that captures their semantic similarity.

If you’re running an ad auction in this space — using power diagrams to allocate territory, where each advertiser’s score at a point is log(bid) - distance^2 / reach^2 and the highest score wins — then the advertiser’s job is to specify a region of this space. Not a keyword. Not a list. A region. And that raises a UX problem that has no analog in the keyword world.

The Dimensionality Wall

You can’t drag a pin across 3,072 axes.

This is the fundamental UX challenge of embedding-based ad systems. In keyword advertising, the advertiser’s interface is a search box and a list. The space of options is large but enumerable. You can browse it, filter it, see related suggestions. The cognitive model is simple: pick words that your customers would type.

In embedding space, direct manipulation fails completely. Even if you project the space down to 2D for visualization — which is already a lossy, potentially misleading compression — you still can’t ask an advertiser to place a dot on a scatter plot and call that targeting. The dot’s position in the projection doesn’t have a transparent relationship to the high-dimensional region it represents. Moving it 10 pixels to the left might shift your audience from marathon runners to yoga practitioners, or it might do nothing at all, depending on the projection’s local distortion.

So you need an interface that lets advertisers navigate embedding space without ever touching coordinates. The answer is semantic hill-climbing.

Semantic Hill-Climbing

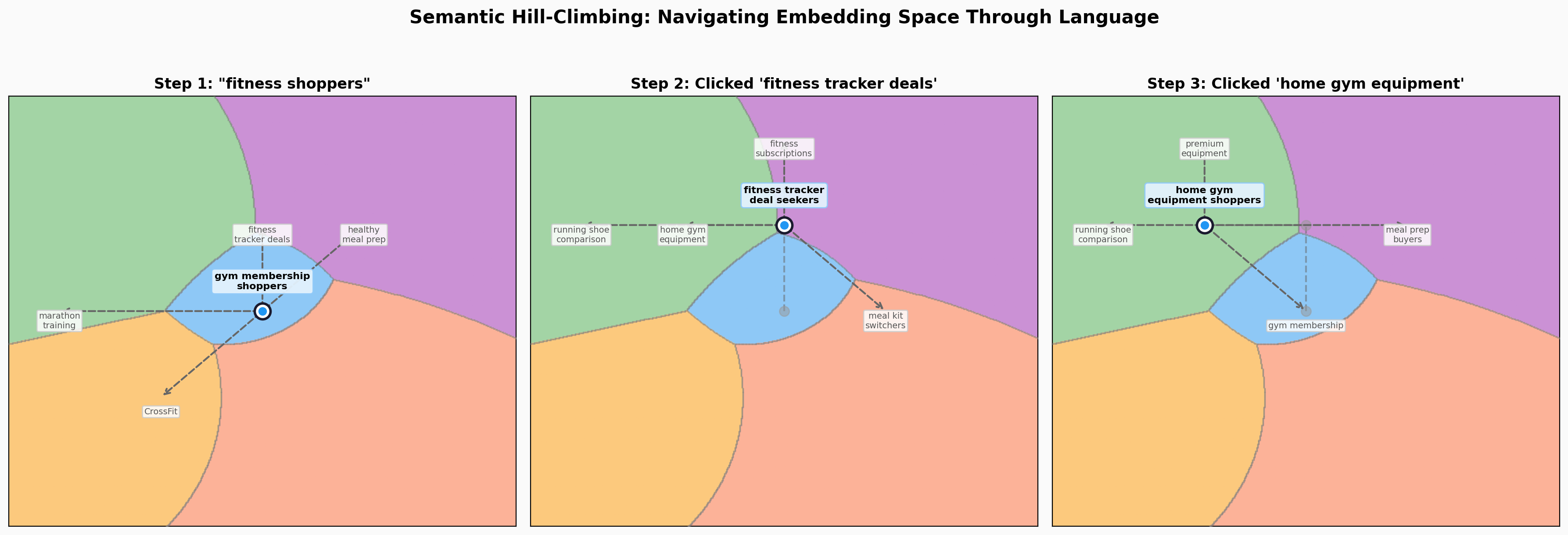

The interaction pattern works like this:

Start with a guess. The advertiser types a natural-language description of their target audience: “high-intent fitness shoppers.” The system maps this phrase into the embedding space — the same way it would embed any piece of text — and places the advertiser’s targeting locus at that position.

See where you are. The system shows the advertiser what their current position means in concrete terms. Not coordinates, not abstract labels, but example queries and conversations that live in this region of the space:

You’re targeting: running shoe comparison shoppers

“Nike Pegasus vs Hoka Clifton” · “best carbon plate shoes 2026” · “Brooks Ghost 16 review”

This is the key grounding mechanism. The advertiser doesn’t need to understand the geometry. They just need to read three example queries and ask: are these my customers?

Choose a direction. The system presents suggestions at two scales — fine-tuning adjustments and exploratory jumps — each with example content and a price tag:

Nearby adjustments:

- CrossFit class bookers — $4.20 CPM — “WOD timer app”, “CrossFit box near me”

- running community members — $3.50 CPM — “Strava running clubs”, “5K race calendar”

Explore new territory:

- meal kit service switchers — $2.10 CPM — “HelloFresh vs Blue Apron”, “weekly meal delivery”

- athleisure fashion browsers — $1.80 CPM — “Lululemon sale”, “best gym leggings 2026”

The advertiser picks one, and the locus moves. New suggestions appear. The price tags update. Repeat.

At any point, the advertiser can break out of the suggestion grid by typing a free-text refinement instead. “More focused on nutrition.” “People who already own a Peloton.” The system re-embeds the description and moves the locus accordingly — an escape hatch that prevents the interface from feeling like a choose-your-own-adventure book with only four choices per page.

After a few rounds, the advertiser has navigated to a region that matches their intent — verified not by trusting a coordinate system, but by reading example content and price signals. The locus represents a position they’ve validated through a sequence of meaningful choices.

What You’re Actually Buying

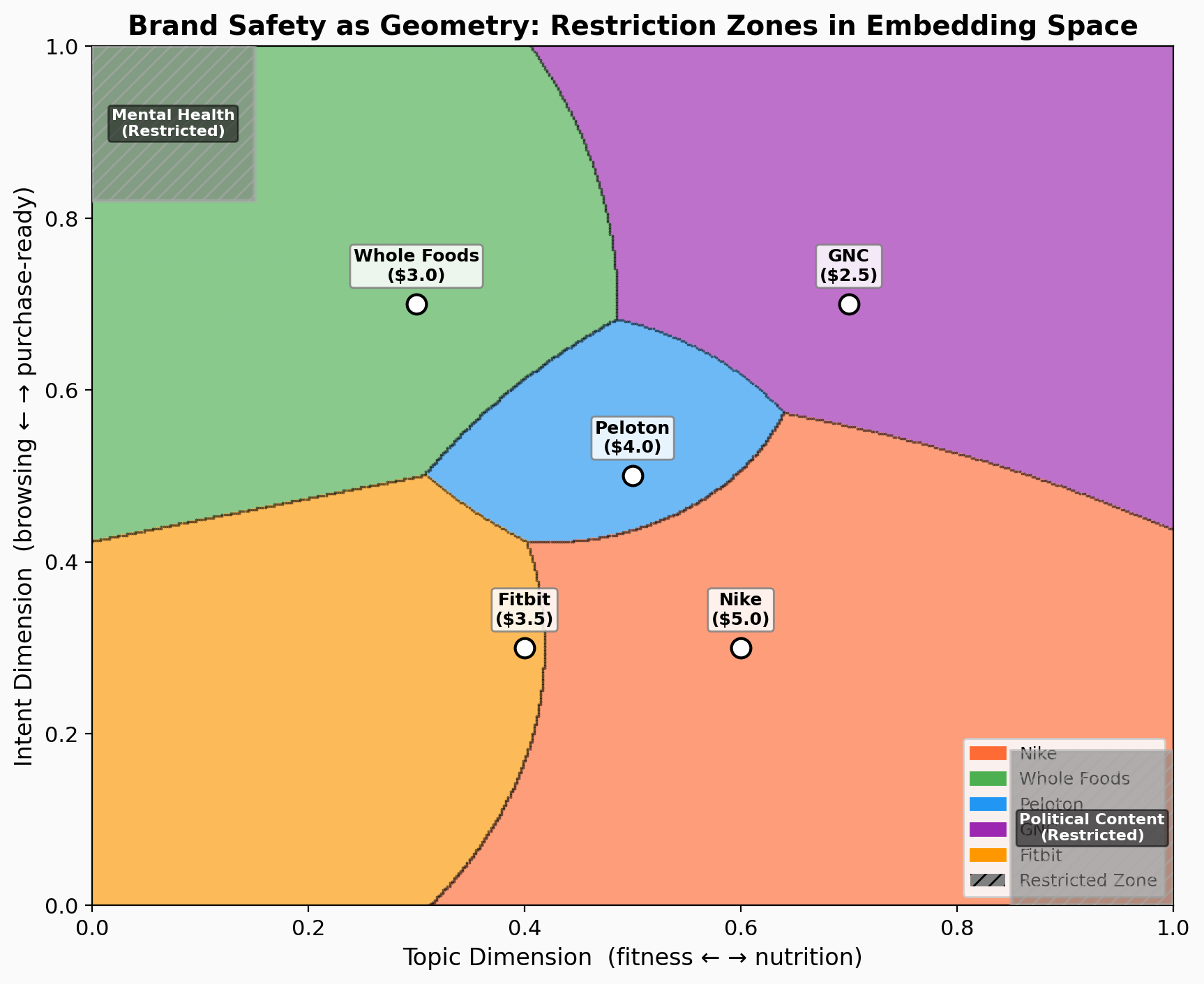

Once the advertiser locks in their position, the platform shows them what they’re getting. The 2D projection — which was just a feedback mechanism during navigation — now serves as a map of the competitive landscape.

Your territory is the region of the space where your power diagram score is highest. It’s computed from three things: your bid, your position (the targeting locus you just set), and your reach (a parameter controlling how aggressively your score decays with distance). The platform renders this territory with impression density overlaid, so you can see not just where you own space, but how much traffic flows through it.

In keyword auctions, competition is invisible. You bid $2 on “running shoes,” someone else bids $2.50, and you lose. You can’t see who you’re competing against or what they’re doing. Here, competition is spatial and legible. You can see that Nike owns the running-shoe region, that GNC is encroaching from the nutrition side, and that there’s an underserved gap in the home-fitness area where no one has planted a flag. You can move your targeting locus into that gap. You can specialize your reach to be narrow along the topic axis and broad along the intent axis, creating an elongated territory that captures high-intent users across multiple subtopics.

The CPM estimates reinforce this. Each direction card’s price reflects both impression density (more traffic = higher prices) and competitive pressure (more nearby advertisers = higher second-price floor). An uncrowded region with decent traffic is a deal. A crowded region near a high bidder is expensive. The advertiser sees this before committing, not in a retrospective analytics dashboard.

Brand Safety as Geometry

Keyword-based brand safety is a blocklist. You enumerate topics you want to avoid — “violence,” “politics,” “adult content” — and the platform tries to match those labels against content. It’s fragile because the matching is discrete: content that’s semantically adjacent to a blocked topic but doesn’t use the blocked words slips through.

In embedding space, brand safety becomes geometric. A restriction zone is a region of the space — a hypercube, a sphere, an arbitrary convex set — carved out of the auction entirely. No ads are served in that region. Your targeting boundary clips around it.

This is cleaner and harder to game. A restriction zone defined by a region in embedding space catches semantically similar content regardless of the specific words used. “Best ways to cope with depression” and “mental health crisis resources” both fall in the same part of the space, even though they share no keywords with a naively constructed blocklist. The geometry captures meaning, not surface form.

In the prototype, we implement two default restriction zones as axis-aligned rectangles: “Mental Health” in the high-intent, fitness-adjacent corner, and “Political Content” in the low-intent, nutrition-adjacent corner. They render as gray hatched areas on the canvas, visually carving out no-go zones from the territory map. Each advertiser can see the fraction of impressions lost to restrictions — a direct measurement of the cost of brand safety.

An Open Design Problem

The core interaction pattern — semantic hill-climbing through language, examples, and price signals — scales to high dimensions because it never requires the advertiser to engage with dimensions directly. The advertiser’s cognitive model is always “here are example queries, here’s what it costs, do I want to move closer to this or away from it?” That model works whether the underlying space has 2 dimensions or 3,072.

The hard problems that remain are real: how do you select which suggestions to show when the neighborhood is 3,072-dimensional? How do you generate example content that faithfully represents a high-dimensional region? How do you explain to an advertiser that two nearby-looking points on the 2D projection might actually be far apart in the full space?

These are UX problems, not mathematical ones. The auction mechanism is well-defined regardless of dimensionality. The question is how to build an interface that lets humans make good decisions in a space they can’t see. Try the interactive prototype and decide for yourself.